A sensational discovery!

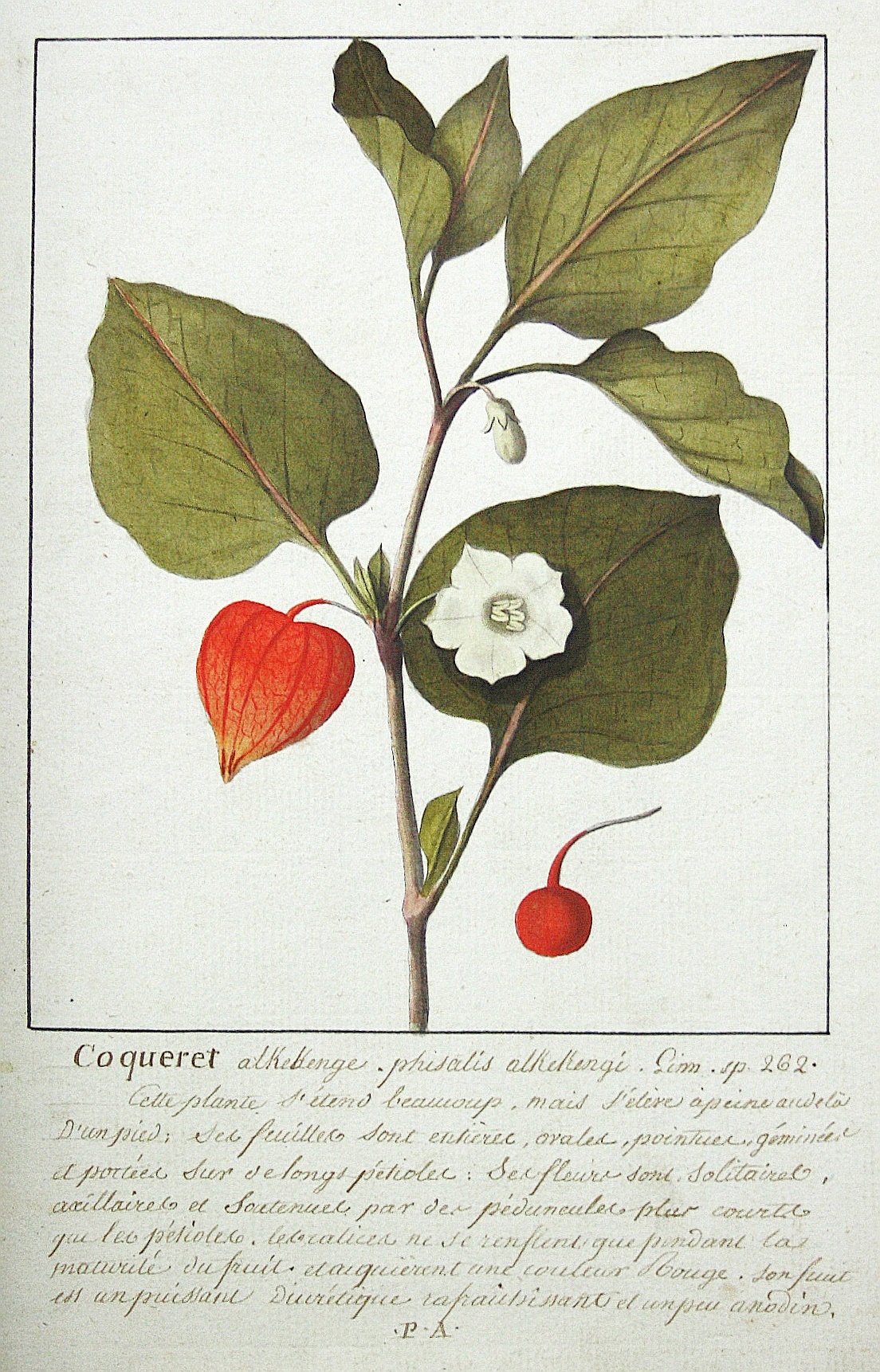

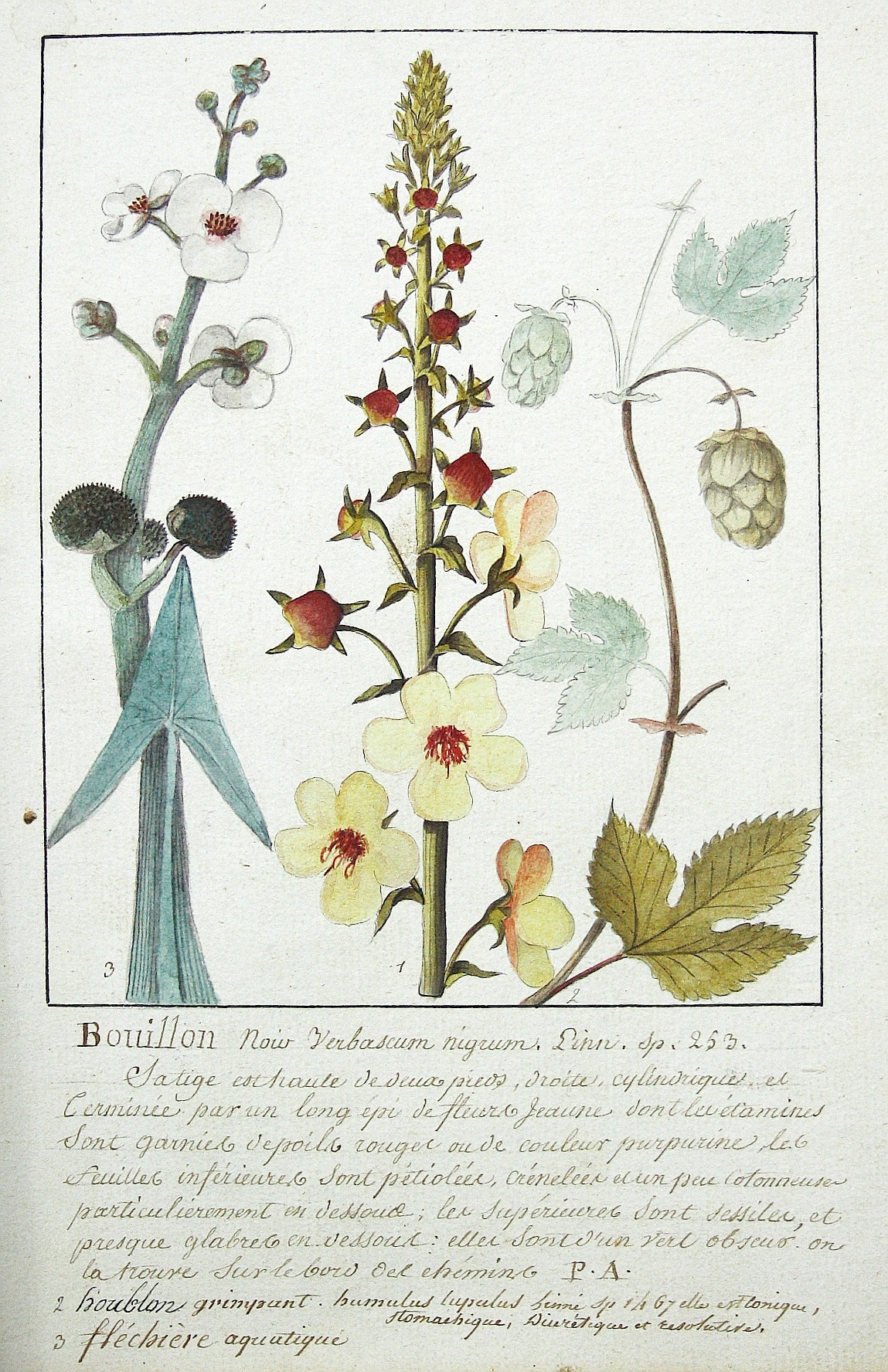

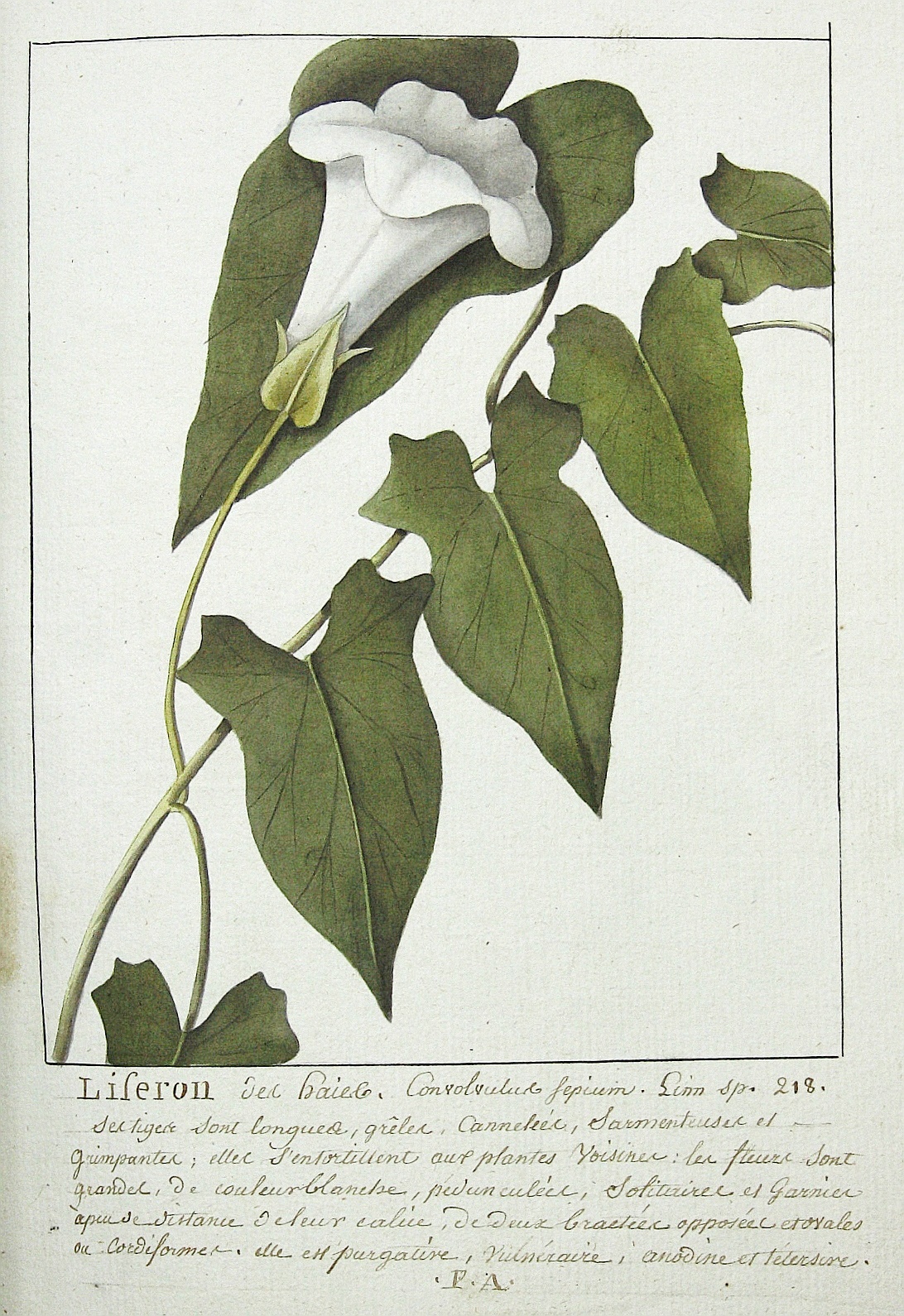

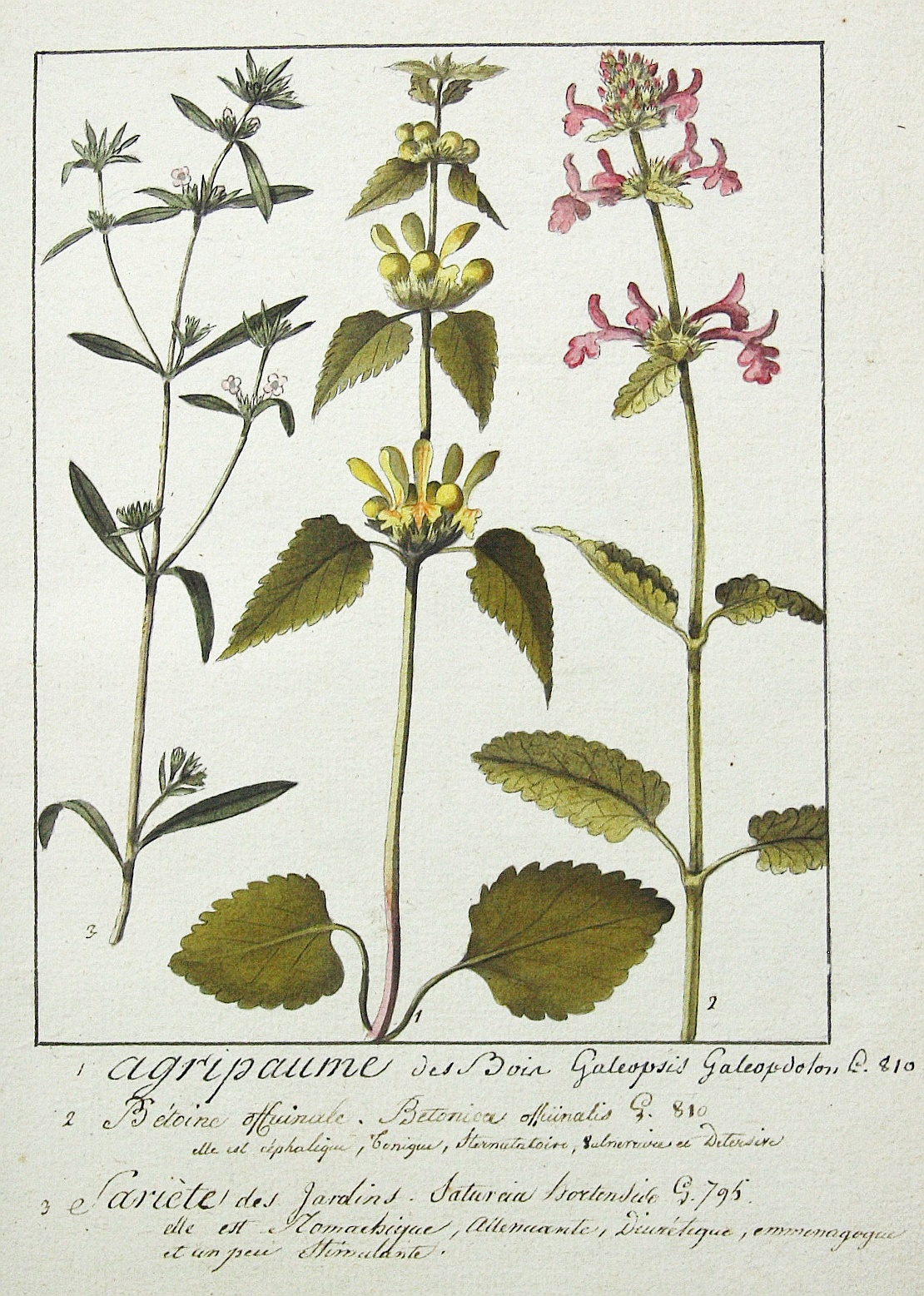

BULLIARD, Jean Baptiste Francois (* 1752 Aubepierre-sur-Aube; † 1793 Paris) and LAMARCK, Jean Baptiste de (* 1744 Bazentin-le-Petit; † 1829 Paris) – 467 original watercolor drawings on 239 leaves, with handwritten descriptions and notes. n.d. (c. 1776-1778). Contemporary leather with blank spine label. 297 x 230 mm.

This very important manuscript represents the previously unknown botanical drawings for Lamarck’s Flore Francaise and demonstrates the hitherto fameless cooperation between two of the foremost French botanists from the 18th century. It gives an exceptional insight into the creative process of Lamarck’s first book and is of the utmost importance for the awareness of Lamarck’s visual imagination of botanical illustration. Furthermore it compensates the lack of early specimens in his herbarium preserved at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris.

After 10 years of research, Lamarck finished the work for his first book Flore Francaise published early in 1779. It was the first scientific French flora and the first book using dichotomous keys. The book incorporates 8 uncolored plates showing small illustrations of plants and their parts.

The present manuscript verifies Lamarck’s temporary intention to publish his Flore Francaise as a color plate book.

Bulliard learned draughtsmanship at the Clairvaux Abbey, a Cistercian monastery in the Aube department in northeastern France. Around 1775 he came to Paris. In 1776, whilst Lamarck was still working on his Flore Francaise, the first parts of Bulliard’s Flora Parisiensis have been published, illustrated with color plates after his own drawings. At the latest from then on Bulliard’s talent as a draughtsman must have attracted Lamarck’s attention.

Until today the cooperation between Lamarck and Bulliard stayed completely unknown. Obviously the collaboration between them was limited to the present drawings. The fact that Bulliard’s drawings finally stayed unpublished could indicate a dispute between both botanists or probably be the cause for a conflict which was never settled afterwards.

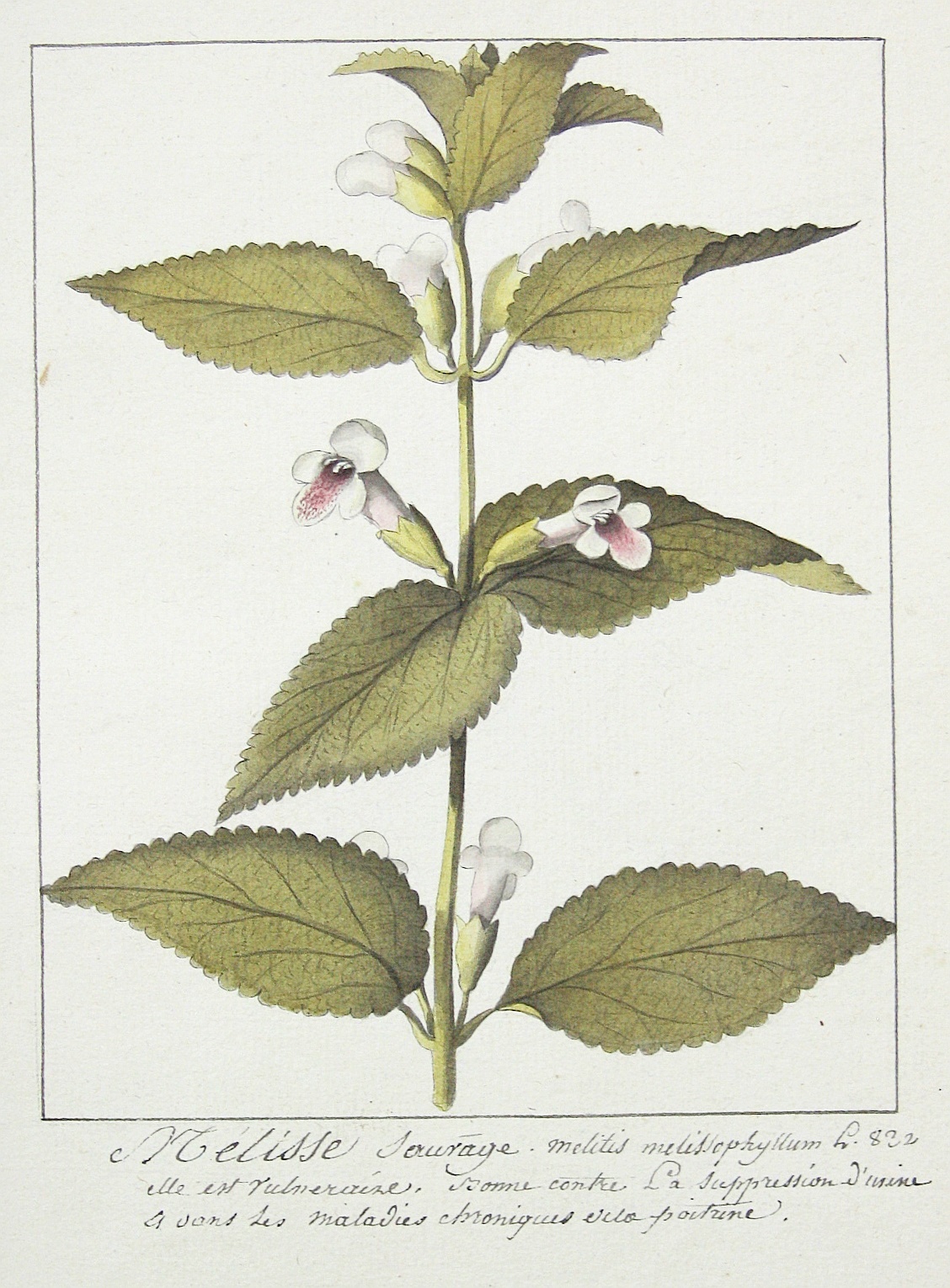

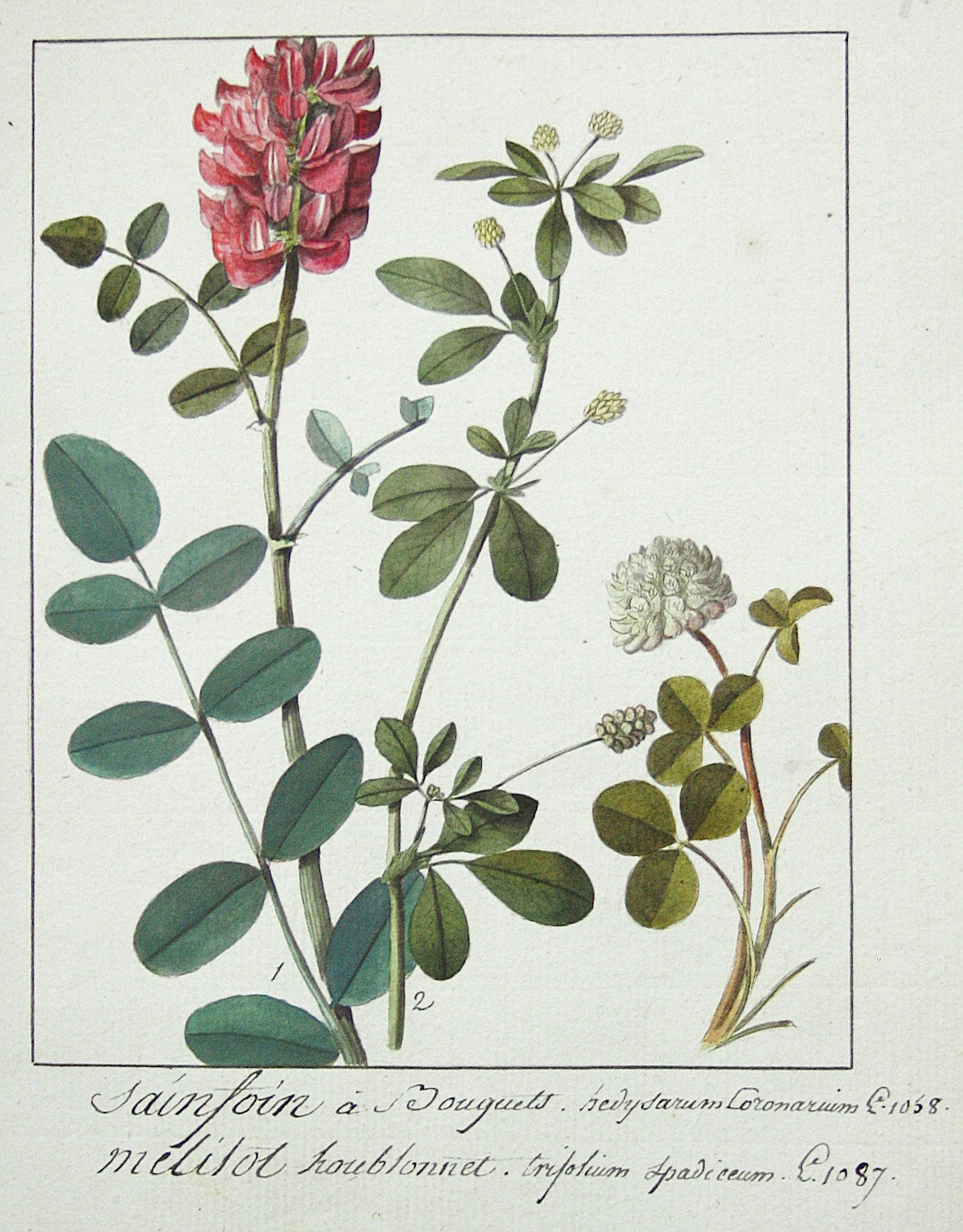

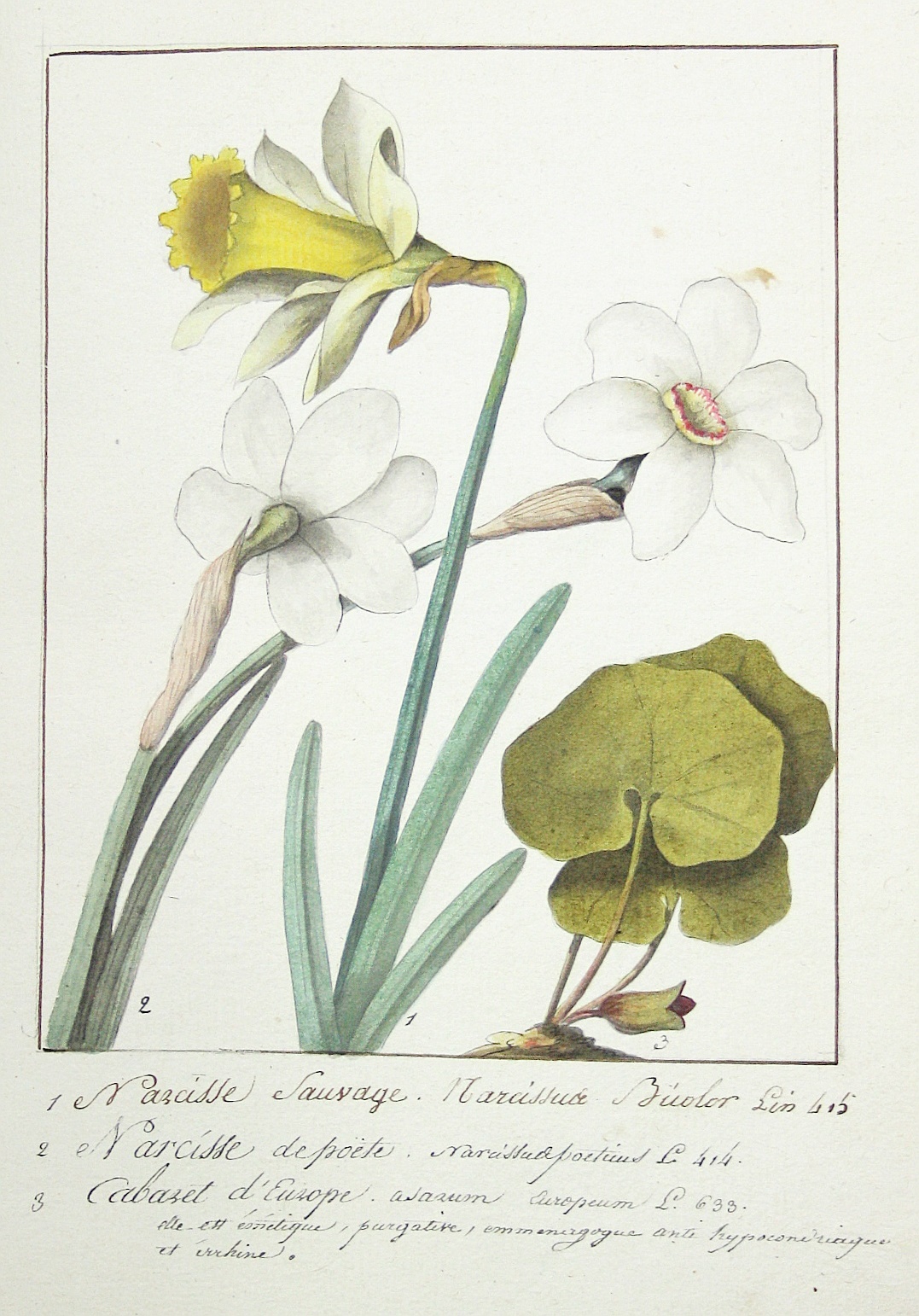

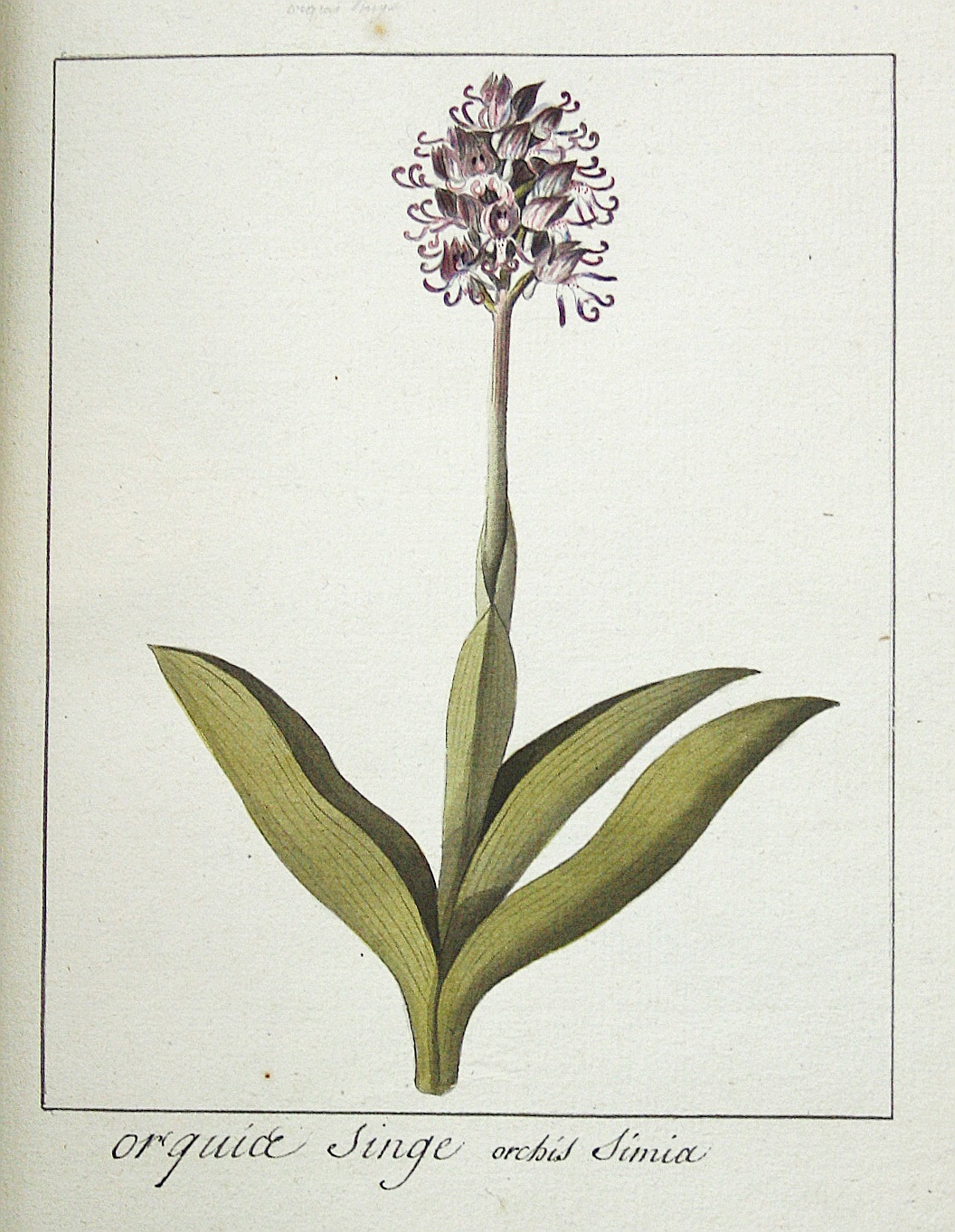

The manuscript comprises 467 watercolor drawings on 239 leaves. It consists of 421 flowering plants and 46 mushrooms. The species descriptions beneath the drawings are working drafts by Lamarck for his Flore francaise written in Bulliards own hand. The descriptions contain the plant’s common name usually followed by the binomial nomenclature by Linnaeus (and sometimes Tournefort). 65 species have larger delineations of the plants characteristics including stems, leaves, fruits and flowers as well as their medical qualities. Most species merely have short descriptions, 15 are only entitled with their vernacular name and 70 plants were not specified at all.

The arrangement of species within the manuscript is already the same as in Lamarck’s French flora. It is based on Lamarck’s new method using dichotomous keys. Bulliard used an already bound volume of blank leaves, choosing for each plant the accurate place within the manuscript according to Lamarck’s instructions. The blind tooled number „I“ on the spine of the binding indicates that Bulliard and Lamarck obviously planned more plate volumes in the beginning.

Every plant illustration is surrounded by a border which is accompanied by a descriptional text beneath the image. The typography of the text, the arrangement of the drawings as well as the size of the present manuscript is the same as for Bulliard’s Herbier de la France, which he started to publish in 1780, only 1 year after Lamarck’s Flore francaise. Obviously Bulliard adopted the typography of the present manuscript for his own publication. The inspiration for the borders most probably came from the works of Francois-Nicolas Martinet, under whome Bulliard improved his draughtsmanship and learned the art of engraving.

Bulliard invented a method of color printing which he later used for his Herbier de la France. It can be supposed that Bulliard and Lamarck planned to color print the present drawings as well. The present drawings were made after Lamarck’s own instructions. None of them include extra images of the plant’s sexual organs. Lamarck criticised Linnaéus’s plant classification system which was based on the plant’s sexual parts and firstly used dichotomous keys instead. Therefore the illustrations for his Flore francaise didn’t need to have illustrations of the plant’s sexual parts. On the contrary Bulliard himself always added extra images of the plant’s sexual organs within the drawings for his own publications.

Eventually during the work on the manuscript the plan for publication seemed to be no longer valid. Whilst the execution of the drawings remain carefully throughout, the species descriptions gradually became more brief and swift. Whilst in the beginning each leave was used for only 1 drawing, Bulliard later added other species alongside to his already finished drawings and subjoined a more brief description, though always following Lamarck’s arrangement of species. The reason for this could be the financial situation of Lamarck. In 1760 he joined the French army and after leaving due to health reasons he received a reduced pension of only 400 francs a year. Whilst working on his Flore francaise Lamarck was a student of botany under Bernard de Jussieu and obviously wasn’t able to finance the publication of a book even less when color plates were accompanied. Finally Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon arranged to have Lamarck’s work published at government expense, and Lamarck received the proceeds from the sales. Possibly the sponsor only wanted to finance an edition without color plates, which would have multiplied the required costs. This in the end could have been caused a dispute between Lamarck and Bulliard. However the present drawings by Bulliard were not part of the publication and stay unrecorded to this day.

Lamarck ranked nomenclature as the most difficult part of botany. He tried to give appropriate names to each species and gave a few general remarks on nomenclature in the ‚Discourse preliminaire‘ of his Flore francaise. There are several differences regarding the nomenclatures of the present manuscript and Lamarck’s Flore francaise. 32 of the species in the present manuscript are entitled with different common names than in the first edition of Flore francaise e.g. „Chardon Roland“ (manuscript) and „Panicaut commun“ (1779) and later „Panicaut des champs“ (1805) or „Scorsonnere d’Espagne“ (manuscript) and „Scorsonniere denticulée“ (1779).* Quite a lot of the species common names in the manuscript and the 1779 edition are identical, but were changed in later editions, e.g. „Pédane alongé“ (manuscript and 1779) but „Onopordone de Dalmatie“ (1805) or „Gentiane centauriette“ (manuscript and 1779) but „Chironie centaurée“ (1805). 16 species we were unable to locate in the 1779 edition but were incorporated in the 1805 edition e.g. „croix de Jerusalem“ (manuscript) and „Lychnide de Chalcedoine“ (1805). Changing the vernacular names over time was not unusual for Lamarck and the present manuscript gives an hitherto impossible insight into Lamarck’s plant taxonomy for his French flora.

The National Museum of Natural History in Paris preserves Lamarck’s herbarium with 19.000 specimens. The part of the Flore francaise period today is very incomplete. Nevertheless we could locate a few specimens which are contained as well as in the present manuscript and Lamarck’s herbarium. One of them is the orchis simia, commonly known under the name monkey orchid. Lamarck was the first to describe it in his French flora and also gave it its Latin name. The manuscript contains a full page drawing of the monkey orchid with the common name „orquis singe“ and the Latin name „orchis simia“, the herbarium bears two different Latin names: „orchis militaris“ and „orchis simia“. The autograph nomenclatures within the manuscript and Lamarck’s herbarium can be related to one and the same person. Comparing them with other autographs by Lamarck and Bulliard they can be refered to Bulliard.** Therefore it can be reasoned that some of the earlier specimens within Lamarck’s herbarium came from Bulliard’s own collection. It is for additional interest that douzens of Bulliard’s specimens in Lamarck’s herbarium have quite similar hand drawn borders like his drawings within the present manuscript and the plates in his Herbier de la France.

During the work on the present manuscript Lamarck still used abbreviations for the plant’s growing seasons: „A“ for annual plants (Une année), „D.A.“ or „B.A.“ for biennial plants (Deux ans) and „P.A.“ for perennial plants (Plus de deux ans). In the 1779 edition of his French flora he already used symbols.

Bulliard engraved all the plates for his publications after his own drawings. Nearly 1300 engraved plates by him are known. In 1922 Fournier mentioned an unpublished manuscript with 300 botanical watercolours which Bulliard made at the Clairvaux Abbey in 1773, but according to J.E. Gilbert they have been lost.*** In 1952 Gilbert could locate 407 original drawings in 12mo by Bulliard in the archives of the Griffaton family which exclusively depicting champignons. They had been published in Bulliard’s Herbier de la France. Gilbert was unable to locate any other Bulliard drawings. Most likely the present manuscript comprises the only still existing drawings by Bulliard depicting flowering plants.

Lamarck and Bulliard attached the greatest of importance to the correctness of the present watercolors. The drawings fulfill the demands of scientific botanical illustration in all aspects and are of great importance for confirming the identities of plants in Lamarck’s Flore francaise and even identifying species which Lamarck refused to include in his flora. Moreover it is an important source for Lamarck’s botanical methodology in his French flora.

The scientific value of the drawings

„The main goal of botanical illustration is not art but scientific accuracy. It must portray a plant with precision and level of detail for it to be recognized and distinguished from another species.“

(Botanic Gardens Conservation International)

Herbaria are essential for studies in taxonomy, systematics, anatomy, morphology, ethnobotany and paleobiology. They enable to discover or confirm the identity of a plant and document the concepts of the botanists who have studied the specimens. It is quite difficult to write a precise species description. It would be much more long and complicated and far more difficult to grasp than a pictorial presentation of the same species. A picture is far more able to present a comprehensive description of a species‘ morphology.

Lamarck and Bulliard attached the greatest of importance to the correctness of the present drawings. The drawings fulfill the demands of scientific botanical illustration in all aspects. The present herbal manuscript therefore is of great importance for confirming the identities of plants in Lamarck’s Flore francaise and even identifying species which Lamarck refused to include in his flora. Moreover it is an important source for Lamarck’s botanical methodology in his French flora.

All major Lamarck manuscripts hitherto known are preserved in national institutions or libraries such as The National Museum of Natural History in Paris and the Harvard University.

The present manuscript is the only major pictorial Lamarck-related manuscript known and therefore of the utmost scientific and historic value.

It is also the only major Lamarck-related manuscript remaining in private hands, and the most significant Lamarck item to have come to the market in over 100 years.

This is most probably the last opportunity to obtain an extensive Lamarck-related manuscript!

* In the 1805 edition of his French flora Lamarck declared within the species description of Onopordone de Dalmatie: „Cette plante est connue sous le nom de chardon-roland“, and within the description of Lychnide de chalcedoine: „…est cultivée dans les parterres sous les noms de croix de Jerusalem,…“ or for Blite en tete: „On cultive cette plante dans quelques jardins sous le nom d’epinard-fraise“. Within the present manuscript Lamarck still used the vernacular names under which the plants had been grown in the different botanical gardens. In his 1779 edition of his Flore francaise he already changed some of the common names to more appropriate ones.

** For Bulliard autographs see: E.J. Gilbert – Un esprit – une oeuvre. Bulliard, Jean Baptiste Francois, dit Pierre (1752-1793) in: Bulletin trimestriel de la Société mycologique de France 68, no. 1(1952)

*** M. l’abbé P. Fournier – Les premiers dessins de Bulliard. Bulletin de la

Société Botanique de France, 69:2, 216-220, (1922)

sold